In this post I’m going to talk about domain-driven design, and how I’ve been using that approach when developing VocalPy. In the last post on VocalPy version 0.10.0, I made a point of saying that I would only describe new features, and I’d save discussion of how I designed them for another post. Well, here’s that post.

I’m writing this post for two audiences. The first is people who are interested in using and/or contributing to VocalPy, that want to better understand its design. The second audience is anyone who is interested in how to design software for scientists, software engineers, and everyone who sits somewhere along the spectrum between those two job titles.

You might think I should save my thougts on this until such time that VocalPy actually supports a community of researchers studying acoustic communication. Instead, I should be busy proving this software is actually useful: writing more docs to show how it’s used, adding a bunch of features, recruiting new users and other maintainers. Fair point.

But I feel like it’s worth taking just a little bit of time to justify my approach in words, to claim there’s a method to my madness. That’s what I said I’d do in the first post on this blog after all. And reading books like “The Architecture of Open Source Applications” has made me think it’s worth talking about stuff like this.

What is domain-driven design?

If you go and read the Forum Acusticum proceedings paper, “Introducing VocalPy”, you’ll see that I name-drop domain-driven design there. But I don’t talk about it a lot, since you only get so much space in a proceedings paper. Please consider this a longer, much more informal, version of what I wrote there.

For this post to make sense, I have to introduce domain-driven design. I also need to repeat myself a little – I wrote about this on my personal blog. If you came here from there, feel free to skip down to where I start talking about how I’ve used domain-driven design when developing VocalPy.

What is domain-driven design, and why should you care about it? Sometime in 2022-2023, I read Domain-Driven Design by Eric Evans, and I got really excited about it. (You can get it from bookshop.org here, and if you’re feeling dangerous you can probably find a PDF of it on a random GitHub repository.) I ended up reading it because I had been reading Architecture Patterns with Python, and they mentioned it in the introduction.

If you do nothing else, read the first chapter of Evans’ book, where he relates the story of how he worked with some electrical engineers to design software they would use to design printed circuit boards (AKA PCBs).

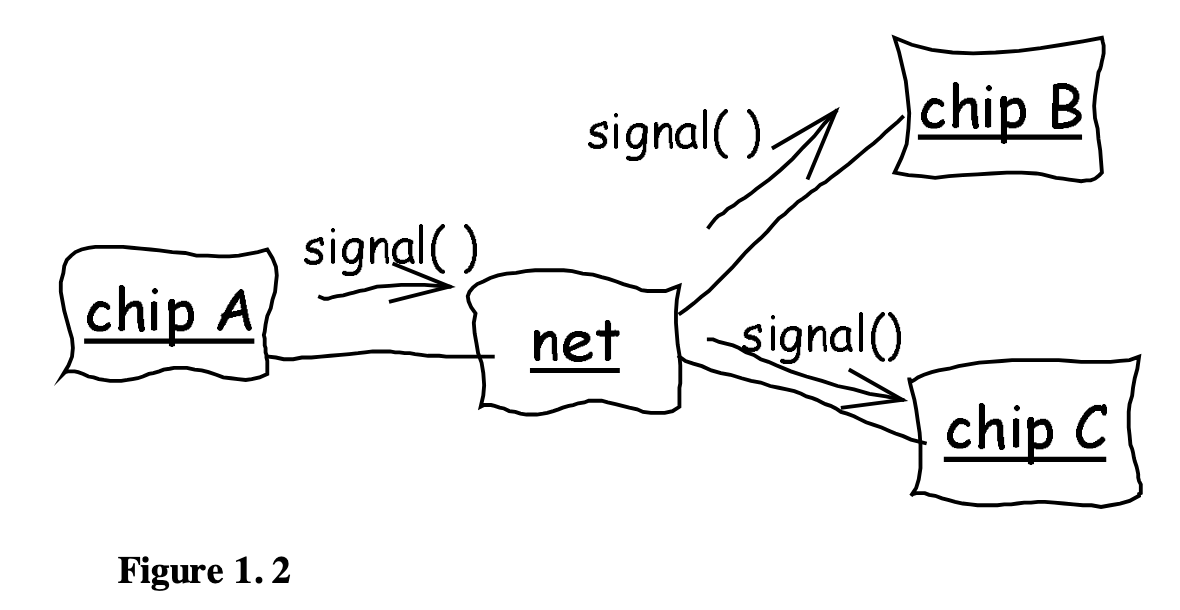

At the beginning, he makes mistakes. He tries to understand their jargon word-for-word. Then he asks them to specify in detail what they think the software should do. Neither of those approaches were ever going to work well. Finally he hits upon the idea of asking them to draw out diagrams of their process and how the software should interact with it. These are simple, rough box and arrow sketches as he shows.

Notice what is happening here: this is not just a developer creating a UML diagram to show to other developers. This is software engineers and domain experts developing a pidgin language together. They use this pidgin to talk about the domain problem they are trying to solve with software.

It’s an interesting story for a couple of reasons. First of all, you have a feeling that he is almost an anthropologist, going into this unfamiliar tribe of electrical engineers so he can learn their culture. I think this is a familiar feeling for anyone who has tried to translate some real-world domain into software, even if it’s part of a culture they feel like they belong to. Second, you really get a feel for his process.

If you have ever gone through the process of designing software for some real-world domain, I bet the story really resonates with you.

How I’ve used domain-driven design when developing VocalPy

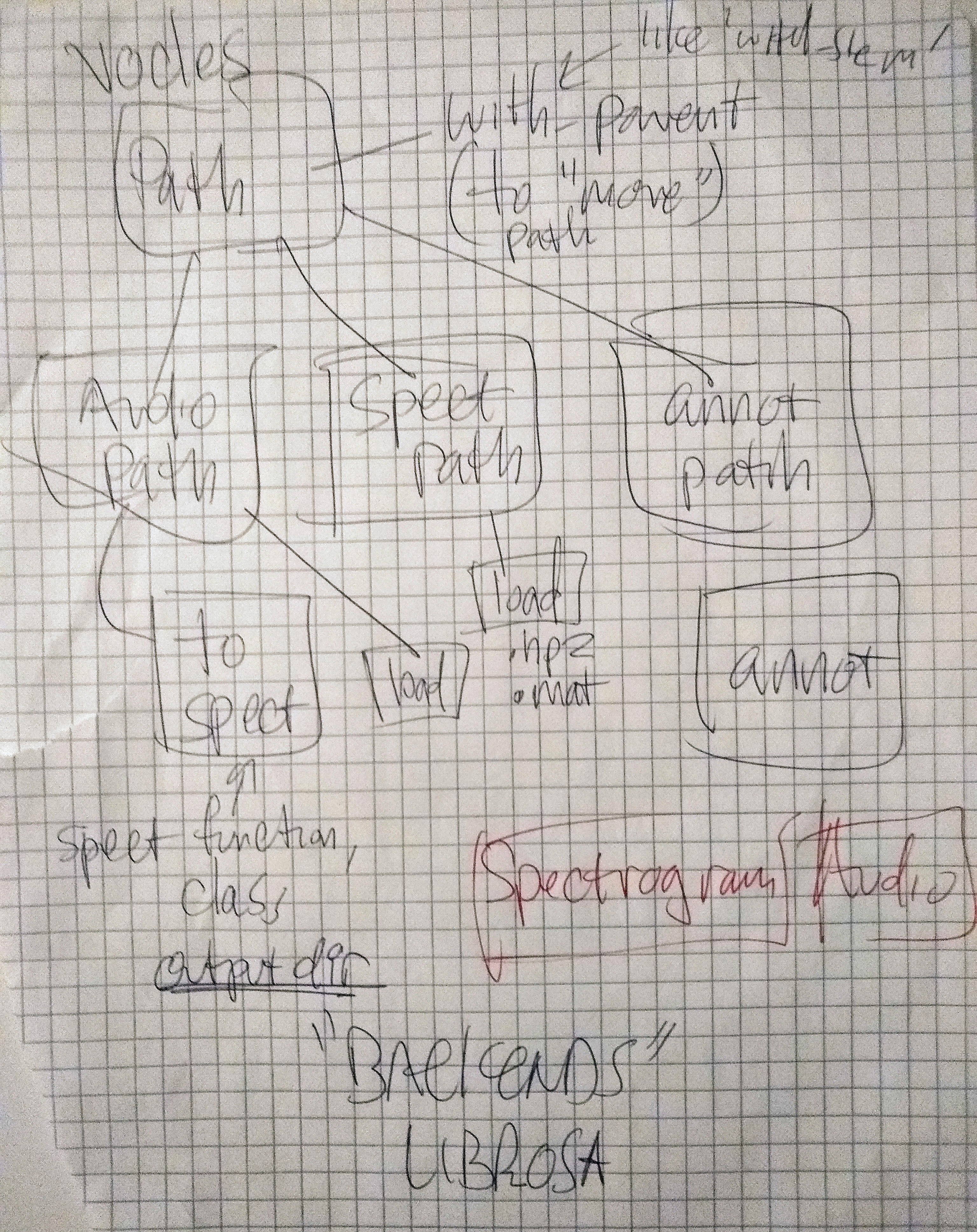

I happened to read Evans’ book at the same time that I had been sketching out some initial ideas for VocalPy. You can see some of these sketches here: https://github.com/vocalpy/vocalpy/issues/19

If you were to click through to the library’s docs, you might notice that these bear little resemblance to VocalPy now. I think this is actually a good thing – more on that below. (You might also notice at the time I was thinking of calling it vocles – everyone please clap for me showing enough restraint for once in my life to not make a bad pun.)

I don’t actually remember which came first: these sketches, or me reading the book. I think that I actually drew the sketches first, and had them sitting around on a desk forever, until finally it hit me that I should add them to the repo to document my design process. And then reading this part of Evans’ book really made me think that drawings like this should be integral to the design process. Part of what I want to say here is that, you should be doing this, if you’re not already, and what’s more, you should be including it in your docs for your software. And this goes for all software, unless you are literally writing such a boring cookiecutter CRUD app that a so-called Large Language Model can regurgitate it perfectly for you, after being “trained” on the actual work of human beings. I would argue that these drawings should be part of the theory behind your scientific software.

Ok, now you have an idea of what domain-driven design is. You might ask yourself, have I done anything with this? Or do I just like pontificating into the void about ideas from computer science and tech books? Even if I haven’t gone back to finish the book and immersed myself in every detail, the core idea has really stuck with me. Going back to that Proceedings paper where I first introduced VocalPy, you can see where I included a similar drawing, cleaned up for a paper.

Even by the time I got to this first Proceeding paper, the design of the library had evolved. But this is a good thing — I did exactly what Evans prescribed, and continued to iterate on the design of the package. Doing so made me realized which parts were actually useful, that I wanted to retain in the core. I think sketching things out has also helped me understand why the things I ended up taking out are still useful, just not in the way I had thought at first. The library at first was very focused on the idea of capturing a dataset of specific file types, and then being able to save this dataset in the form of a SQLite file. You can see where I was really focused on treating the dataset as if it were part of an app, like in the architecture book. I do think this is still important, but it is not the core of what the library does – I realized later that the core data types needed to be things like sounds, spectrograms, annotations, the things that a researcher studying animal communication and using bioacoustics would be talking about. So, basically, I did the anthropological exercise, as in Chapter 1 of Evans’ book, but instead of doing it with other people, I started by doing it with the part of my brain that claims to know things about acoustic communication. (I have since engaged with other people who actually know these things and can give me good feedback.)

You can also see how I’ve continued this way, looking at the diagram I show at the top of that last post on VocalPy version 0.10.0

Making these diagrams helped me understand how to change the key workflow in VocalPy. Basically, I realized that I could remove the abstraction of a single Segment, and replace it with a Sound.segment method. That segment method takes in the output of a segmenting algorithm, represented as an instance of Segments, and then returns a list of Sounds, one for each segment.

This lets me still preserve the outputs of a segmenting algorithm for downstream analysis, while simplifying the library.

The simplification minimizes the cogitive load on users and developers, who no longer have to remember how a Segment is related to Segments and how to get a Sound from a Segment. (For more details on what changed, please see that post. Again, realizing that I could make this change by sketching out the workflows is, in my understanding at least, exactly the kind of iterative development process that Evans advocates for in his book.

If domain-driven design is just doodles, then you should put doodles in your docs

Having read this, you might feel like: “Cool story bro, but domain-driven design is not a new idea. I already do that.” I talk about that more in that post on my personal blog. To sum it up, here I’ll say, sure, domain-driven design is not a new idea (as Evans himself acknowledges right at the start of his book). But I also want to use what I’ve said about VocalPy to make the case once more for why I think we should be doing more of it.

Here I want to link to a talk I gave, fittingly titled “VocalPy as a case study of domain-driven design in scientific Python”. (Huge thank you to the DoePy exchange and Don’t Use this Code for inviting me and giving me space to talk through these things with a sympathetic community.)

One of the things I explain in the talk is how my attempt to apply domain-driven design has led me to do things that maybe clash with some recommendations for programming in scientific Python.

Compare for example with Gaël Varoquaux’s recommendations in this SciPy 2017 talk:

The main thing I am doing that would be considered a no-no is: not restricting myself to using the core types of the scientific Python stack, e.g., the NumPy array and the pandas DataFrame. Instead, I have a core set of types in terms of the domain, bioacoustics and acoustic communication in animals: Sounds, Spectrograms, (acoustic) Features, etc. These types are basically data containers, where the underlying array or dataframe is just one attribute away, often literally named data, i.e., Sound.data. My argument is that this is a small price to pay,

if it makes the code more immediately readable to other researchers in my domains of interest.

There are other recommendations that Gaël makes in his talk that I should probably take to heart. I can think of some classes in VocalPy that probably should just be functions. Please don’t think I’m claiming that domain-driven design is some magic method you can follow to produce correct research code. I definitely do not claim to be any smarter or more experienced of a developer than Gaël Varoquaux. This is just me trying to wrap my head around designing software for different domains, and how to reconcile that with different programming paradigms.

(Yes, this is foreshadowing for another blog post.)

In the discussion at the end of that talk, I said just what I’ve said here, that a lot of people react as if, “so, yeah, we already do that”. If that’s so, then show me the doodles! Show me your mental model of your domain — put it in your docs! Let me read it, let me actually see these schematics, even if they are just doodles, it helps me to know how your thought process evolved. All I can see right now is this insurmountable mountain of code, and I don’t even know where the path starts so I can scale it! I know that there are examples of people doing this, e.g., in the scientific Python community where I spend most of my time, but I think it’s fair to say that this is not the norm. I don’t know that I have ever seen diagrams showing how the design evolved, as part of an iterative development process. I can’t help but feel like that’s exactly the sort of thing that could help people get up to speed on how the code works. Again: I tried to give some concrete examples of this in that post on my personal blog. But I hope that here I’ve given you some idea of how I use domain-driven design to develop VocalPy, and more generally what domain-driven design for research code can look like.